Richard Tuttle

Posted: October 20, 2017 Filed under: 2010-, Conceptual, Installation, Sculpture, USA Leave a comment

Relations often invite

comparison, an idea

I learned from Agnes

Martin, who could

decline showing for

this reason. For me,

comparison, in this

case, is outweighed

by an augmentation,

where the access to

each artist’s work is

facilitated, indeed,

enhanced, by the

other’s, so many of

the issues, present

for each artist, shown

in a necessary com-

pliment, otherwise

left open and blank.

Richard Tuttle

exhibition page

Yoshitomo Nara: It Comes in the Dead of Night – Midnight Thinker

Posted: April 14, 2017 Filed under: 2010-, figurative, Japan, Painting | Tags: Yoshitomo Nara 2 Comments

When I focus my thinking, sometimes I slip out of normal time into a world with no clocks, as if in a time warp. In that frozen time, I begin a game of catch with the inspiration that comes from somewhere.

The sky throws me the ball; I throw it back to the sky.

The sky throws me the ball; I throw it back within myself.

The ball comes from within myself; I throw it back into myself.

The ball comes from within myself; I throw it back to the universe.

In any case, this game of catch isn’t with another person, but a conversation I have with myself, or a discussion with the universe. I gaze into the mirror, and become more conscious of myself and the world that spreads out infinitely around me.

Living in a countryside so rural that foxes wander about, I feel that eternity when it’s utterly dark outside, sometimes with the moon shining and the stars twinkling. Before I know it, the rock music blasting out of my stereo gets sucked away somewhere, and I hear only the voices of the animals and the sounds of the rain and wind.

To catch inspiration, I open my arms in my imagination, increasing the antenna’s sensitivity. The overwhelming solitude of those moments turns into pleasure, and lets me become one with the night. I pick up my brush before I lose that sensation, and have a conversation with the me that’s inside the picture.

In this city called New York, I will be presenting paintings, drawings, and sculptures born in these moments, along with ceramics I was so excited to create that it felt like a hobby. I hope that my inspiration reaches the audience.

Yoshitomo Nara, 2017

Exhibition

Read interview

how to write an artist statement

Posted: March 20, 2017 Filed under: Advice, Uncategorized Leave a commentWriting about art is hard. Writing about art that you made can be even harder. We hear artists say, “If I knew how to describe my work in words, I’d be a writer, not an artist.” While this may be true, what’s “truer” is the fact that at some point, you as an artist will be asked to write an artist statement—and whether or not it is good, will matter. So, what makes an artist statement “good”? Whether you’re applying for a residency or grant, or you just want to perfect your elevator pitch, here are a handful of things not to include in your artist statement, plus a few tips to make the process a little less excruciating.

1. Your Artist Statement Is Not “A Piece”

Resist the temptation to use this as an opportunity to write a poem or subvert the “institution of the artist statement.” We get it; you’re an artist. We really do just genuinely want to know what your art is about. Please tell us.

Antoine d’Agata

Posted: February 8, 2016 Filed under: 2010-, France, Photography, Uncategorized, USA Leave a comment

The night, the sex, the wandering… and the need to photograph it all, not so much the perceived act but more like a simple exposure to common and even extreme experiences… It is an inseparable part of photographic practice, in a certain sense, to grasp at existence or risk, desire, the unconsciousness and chance, all of which continue to be essential elements. No moral posturing, no judgement, simply the principle of affirmation, necessary to explore certain universes, to go deep inside, without any care. A ride into photography to the vanishing point of orgasm and death.

I try to establish a state of nomadic worlds, partial and personal, systematic and instinctual, of physical spaces and emotions where I am fully an actor. I avoid defining beforehand, what I am about to photograph. The shots are taken randomly, according to chance meetings and circumstances. The choices made, considering all the possibilities, are subconscious. But the obsessions remain constant: the streets, fear, obscurity, and the sexual act…. Not to mention perhaps, in the end, the simple desire to exist.

Beyond the subject, the lost souls and the nocturnal drifting, the scenes of fellatio and of bodies in utter abandon, I seek to reveal some kind of break up through the mixture of bodies and feelings, to reveal fragments of society that escape from any analysis and instant visualization of the event, but nonetheless, are its principal elements.

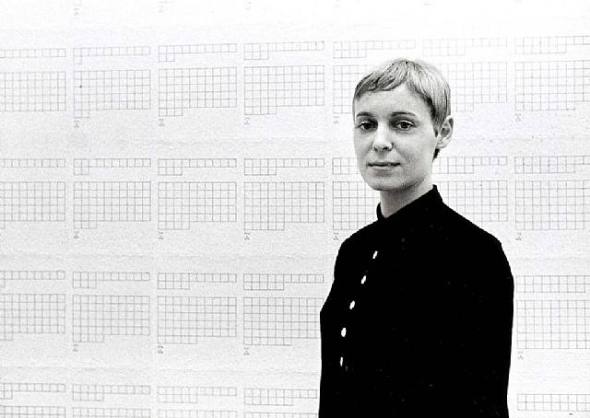

Hanne Darboven

Posted: February 2, 2016 Filed under: 1960-9, 1970-9, 1980-9, 1990-9, 2000-9, Conceptual, Germany Leave a comment

I built up something by having disturbed something: destruction becomes construction. Action interrupts contemplation, as the means of accepting something among many given alternatives, for accepting nothing becomes chaos. A system became necessary: how else could I in a concentrated way find something of interest which lends itself to continuation? My systems are numerical concepts, which work in terms of progressions and/or reductions akin to musical themes with variations. In my work I try to expand and contract as far as possible between limits known and unknown. Generally, I couldn’t talk about limits I know. I only can say at times I feel closer to them, particularly while doing or after having done some conceptual series…. The most simple means for setting down my ideas and conceptions, numbers and words, are paper and pencil. I like the least pretentious and most humble means, for my ideas depend on themselves and not upon material; it is the very nature of ideas to be non-materialistic. Many variations exist in my work. There is consistent flexibility and changeability, evidencing the relentless flux of events.

Hamburg, 1968, as quoted in “Artists on Their Art,” Art International 12, no.4 (20 April 1968): 55.

photo credit: D. Lasagni

Anselm Kiefer: Art is Spiritual

Posted: January 25, 2015 Filed under: 2010-, Conceptual, Germany, multimedia, Painting | Tags: Anselm Kiefer Leave a commentLouise Bourgeois: Artist’s Statement

Posted: January 13, 2015 Filed under: 1950-9, USA | Tags: Louise Bourgeois Leave a commentAn artist’s words are always to be taken cautiously. The finished work is often a stranger to, and sometimes very much at odds with what the artist felt, or wished to express when he began. At best the artist does what he can rather than what he wants to do. After the battle is over and the damage faced up to, the result may be surprisingly dull—but sometimes it is surprisingly interesting. The mountain brought forth a mouse, but the bee will create a miracle of beauty and order. Asked to enlighten us on their creative process, both would be embarrassed, and probably uninterested. The artist who discusses the so-called meaning of his work is usually describing a literary side-issue. The core of his original impulse is to be found, if at all, in the work itself.

Just the same, the artist must say what he feels:

My work grows from the duel between the isolated

individual and the shared awareness of the group. At first I made single figures without any freedom at all: blind houses without any openings, any relation to the outside world. Later, tiny windows started to appear. And then I began to develop an interest in the relationship between two figures. The figures of this phase are turned in on themselves, but they try to be together even though they may not succeed in reaching each other.

Gradually the relations between the figures I made became freer and more subtle, and now I see my works as groups of objects relating to each other. Although ultimately each can and does stand alone, the figures can be grouped in various ways and fashions, and each time the tension of their relations makes for a different formal arrangement. For this reason the figures are placed in the ground the way people would place themselves in the street to talk to each other. And this is why they grow from a single point—a minimum base of immobility which suggests an always possible change.

In my most recent work these relations become clearer and more intimate. Now the single work has its own complex of parts, each of which is similar, yet different from the others. But there is still the feeling with which I began-the drama of one among many.

The look of my figures is abstract, and to the spectator they may not appear to be figures at all. They are the expression, in abstract terms, of emotions and states of awareness. Eighteenth-century painters made “conversation pieces”; my sculptures might be called “confrontation pieces.”

Louise Bourgeois, 1954

SOURCE: Reading Abstract Expressionism: Context and Critique, Ellen G. Landau, ed., New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2005, 180f. Originally published in Design Quarterly, no. 30 (1954), 18.

The Anti-artist-statement Statement

Posted: April 2, 2013 Filed under: 2010-, Uncategorized, USA | Tags: Hyperallergic, Iris Jaffe 1 CommentI hate artist statements. Really, I do.

As an artist, they are almost always awkward and painful to write, and as a viewer they are similarly painful and uninformative to read.

I also don’t know who decided that artists should be responsible for writing their own “artist statement.” Maybe it was an understaffed gallery in the 1980s, or a control freak think-inside-my-box-or-get-out MFA program director, but regardless of how this standardized practice came to be, the artist’s statement as professional prerequisite (at least for artists who have yet to be validated by the established art world) has long overstayed its welcome. And I don’t think a new one should be required in its place. (read)

by Iris Jaffe

from Hyperallergic

Christine Sun Kim: Listening with One’s Eyes

Posted: October 20, 2012 Filed under: 2010-, performance, Sculpture, sound, USA | Tags: Christine Sun Kim, deafness, sign language 1 CommentConsidering the fact that I was born deaf, my learning process is shaped by American Sign Language interpreters, subtitles on television, written conversations on paper, emails, and text messages. These communication modes have often conveyed, filtered, and limited information, which naturally leads to a loss of content and a delay in communication. Thus, my understanding of reality is filtered, and potentially distorted. This is part of the core of my practice as an artist and I am now taking ownership of sounds after years of speech therapy. Instead of seeking for one’s approval to make “correct” sounds, I perform, vocalize, and/or visually translate them based on my perception.

As a visual and performance artist, it is always my intention to approach sound by constantly pushing it to a different level of physicality, and despite my complex relationship with Deaf culture, I attempt to translate sound while unlearning society’s views and etiquettes around it. Using my conceptual judgment and compromised understanding, I challenge and question its visual absence and sometime tactile presence. Fortunately, with today’s advanced technology such as computer programs and high bass speakers, I have been given alternative access to sound. It does not necessarily mean that it’s a mere substitute or replacement of sound.

Taryn Simon: White Tiger

Posted: May 6, 2012 Filed under: 2010-, Photography, USA | Tags: Taryn Simon 1 CommentWhite Tiger (Kenny)

Selective Inbreeding, Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge and Foundation

Eureka Springs, Arkansas

In the United States, all living white tigers are the result of selective inbreeding to artificially create the genetic conditions that lead to white fur, ice-blue eyes and a pink nose. Kenny was born to a breeder in Bentonville, Arkansas on February 3, 1999. As a result of inbreeding, Kenny is mentally retarded and has significant physical limitations. Due to his deep-set nose, he has difficulty breathing and closing his jaw, his teeth are severely malformed and he limps from abnormal bone structure in his forearms. The three other tigers in Kenny’s litter are not considered to be quality white tigers as they are yellow-coated, cross-eyed, and knock-kneed.

Chromogenic print, 37-1/4 x 44-1/2 inches framed (94.6 x 113 cm), Edition of 7

[Taryn Simon provides expansive descriptions as part of many of her works. – eds.]

Louis le Brocquy: notes on painting and awareness

Posted: April 28, 2012 Filed under: 1970-9, figurative, Ireland, Painting, Uncategorized | Tags: Louis le Brocquy, Samuel Beckett, W.B. Yeats Leave a comment

Some seventeen years ago I was still painting the torso as an image of the human presence, when I stumbled into what I call a blind year – a year in which I had no luck, in which no image emerged. At the end of that year I destroyed forty-three bad paintings. As you can imagine, I was by then in a bad way myself, when my wife Anne Madden – herself a painter – brought me to Paris as to a place of discovery. And there indeed I did discover at the Musée de l’Homme, the Polynesian image of the human head, which like the Celtic image which I discovered the following year, represented for me – as perhaps for these two widely different cultures – the mysterious box which contains the spirit: the outer reality of the invisible interior world of consciousness.

In Dublin, now some sixty years ago, the great physicist, Erwin Schroedinger, astonished me with the thought:

Consciousness is a singular of which the plural is unknown and what appears to be the plurality is merely a series of different aspects of this one thing.

Much later in Provence, faced with the Celto-Ligurian head cult of Entremont and Roquepertuse, I asked myself if it were not perhaps this “singular” which so preoccupied our barbarian ancestors in their oracular use of the severed head.

Such a concept of an autonomous, disseminated consciousness surpassing individual personality would, I imagine, tend to produce an ambiguity involving a dislocation of our individual conception of time (within which coming and going, beginning and end, are normally regarded) and confronting this “normal” view with an alternative, contrary sense of simultaneity or timelessness; switching the linear conception of time to which we are accustomed to a circular concept returning upon itself, as in Finnegans Wake.

Likewise, if indeed the aesthetic image in a painting by Rembrandt is illuminated by Joyce’s radiance or whatness, and if that revelation of whatness is achieved by an ambivalence in the role of the paint (involving a transmogrification of the paint itself into the image and vice versa), then these circumstances also may be said to produce that timeless or paratemporal quality, which we instinctively recognize in such a painting.

It would therefore seem that the realization of the aesthetic image or whatness of things, outside and to one side of the linear progress of time, is an essential characteristic of the art of painting and, I imagine, of art generally.

In the modern world, however, we appear to resist such significant integrating imagery, which was more evident perhaps in past cultures, wherein people seem to have regarded the passage of time rather more ambivalently, as being at once related to their personal predicament and to a larger cosmology.

It would appear that this ambivalent attitude to time was especially linked to the prehistoric Celtic or Gallic world, and there is further evidence that it persists to some extent in the Celtic mind today. It is consistent, I think, with Yeat’s tragic view of life – an essentially cosmologic and aristocratic attitude in opposition to the narrow expediency of the “greasy till”:

We Irish, born into the ancient sect

But thrown upon this filthy modern tide

And by its formless spawning fury wrecked

Climb to our proper dark, that we may trace

The lineaments of a plummet-measured face.

In my own small world of painting I myself have learned from the canvas that emergence and disappearance – twin phenomena of time – are ambivalent, that one implies the other and that the state or matrix within which they co-exist dissolves the normal sense of time, producing a characteristic stillness, characteristic of the art of painting.

After a number of years I recall Beckett’s Watt, regarding from a gate the distant figure of a man or a woman (or could it be a priest or a nun?) which appeared to be advancing by slow degrees from the horizon, only surprisingly “without any interruption of its motions” to disappear over it instead. Here going is confounded – if not identified – with coming, backwards with forwards. The film returns the diver to the divingboard. The procession of present moments is reversed, stilled.

Elsewhere in Finnegans Wake does not the fallen Finegan become “Finn Macool lying beside the Liffey, his head at Howth, his feet at Phoenix Park, his wife beside him, watching the microcosmic ‘fluid succession of presents’ go by like a river of life”?

And is not Yeats’s circular lunar system of re-incarnation – the winding stair of Thoor Ballylee, climbed and descended repeatedly – itself a cosmic arrangement of this fluid succession of presents, of time-consciousness in this profoundly Celtic sense? Is this indeed the underlying ambivalence which we in Ireland tend to stress; the continual presence of the historic past, the indivisibility of birth and funeral, spanning the apparent chasm between past and present, between consciousness and fact?

image: Image of Samuel Beckett, Stirrings Still, 1994, oil on canvas, 116 x 89 cm

Guy Laramee: the cloud of unknowing

Posted: January 5, 2012 Filed under: 2010-, Canada, Conceptual, Installation, Sculpture | Tags: Guy Laramee Leave a commentThe erosion of cultures – and of “culture” as a whole – is the theme that runs through the last 25 years of my artistic practice. Cultures arise, become obsolete, and are replaced by new ones. With the vanishing of cultures, some people are displaced and destroyed. We are currently told that the paper book is bound to die. The library, as a place, is finished. One might say: so what? Do we really believe that “new technologies” will change anything concerning our existential dilemma, our human condition? And even if we could change the content of all the books on earth, would this change anything in relation to the domination of analytical knowledge over intuitive knowledge? What is it in ourselves that insists on grabbing, on casting the flow of experience into concepts ?

When I was younger, I was very upset with the ideologies of progress. I wanted to destroy them by showing that we are still primitives. I had the profound intuition that as a species, we had not evolved that much. Now I see that our belief in progress stems from our fascination with the content of consciousness. Despite appearances, our current obsession for changing the forms in which we access culture is but a manifestation of this fascination.

My work, in 3D as well as in painting, originates from the very idea that ultimate knowledge could very well be an erosion instead of an accumulation. The title of one of my pieces is “ All Ideas Look Alike”. Contemporary art seems to have forgotten that there is an exterior to the intellect. I want to examine thinking, not only “What” we think, but “That” we think.

So I carve landscapes out of books and I paint Romantic landscapes. Mountains of disused knowledge return to what they really are: mountains. They erode a bit more and they become hills. Then they flatten and become fields where apparently nothing is happening. Piles of obsolete encyclopedias return to that which does not need to say anything, that which simply IS. Fogs and clouds erase everything we know, everything we think we are.

After 30 years of practice, the only thing I still wish my art to do is this: To project us into this thick Cloud of Unknowing.

Georges Braque: thoughts and reflections on painting

Posted: October 14, 2011 Filed under: 1910-1919, cubism, France, Painting | Tags: Georges Braque Leave a commentIn art, progress does not consist in extension, but in the knowledge of limits.

Limitation of means determines style, engenders new form, and gives impulse to creation.

Limited means often constitute the charm and force of primitive painting. Extension, on the contray, leads the arts to decadence.

New means, new subjects.

The subject is not the object, it is a new unity, a lyricism which grows completely from the means.

The painter thinks in terms of form and color.

The goal is not to be concerned with reconstituting an anecdotal fact, but with constituting a pictorial fact.

Painting is a method of representation.

One must not imitate what one wants to create.

One does not imitate appearances; the appearance is the result.

To be pure imitation, painting must forget appearance.

To work from nature is to improvise.

One must beware of an all-purpose formula that will serve to interpret the other arts as well as reality, and that instead of creating will only produce a style, or rather a stylization…

The senses deform, the mind forms. Work to perfect the mind.

There is no certitude but in what the mind conceives.

The painter who wished to make a circle would only draw a curve. Its appearance might satisfy him, but he would doubt it. The compass would give him certitude. The pasted [papiers collés] in my drawings also gave me a certitude.

Trompe l’oeil, is due to an anecdotal chance which succeeds because of the simplicity of the facts.

The pasted papers, the faux bois— and other elements of a similar kind— which I used in some of my drawings, also succeed through the simplicity of the facts; this has caused them to be confused with trompe l’oeil, of which they are the exact opposite. They are also simple facts, but are created by the mind, and are one of the justifications for a new form in space.

Nobility grows out of contained emotion.

Emotion should not be rendered by an excited trembling; it can neither be added on nor be imitated. It is the seed, the work is the blossom.

I like the rule that corrects the emotion.

from “Pensées et réflexions sur la peinture,” Nord-Sud 10 (December 1917).

Reprinted in Artists on Art, Pantheon, NY, 1958, pp. 422-423

John McLaughlin: the marvelous void

Posted: October 1, 2011 Filed under: 1960-9, 1970-9, abstract, minimal, Painting, USA | Tags: John McLaughlin Leave a comment

My purpose is to achieve the totally abstract. I want to communicate only to the extent that the painting will serve to induce or intensify the viewer’s natural desire for contemplation without the benefit of a guiding principle.

Yves Klein: The Chelsea Hotel Manifesto

Posted: September 14, 2011 Filed under: 1960-9, abstract, France, Painting | Tags: Yves Klein Leave a comment

Due to the fact that I have painted monochromes for fifteen years,

Due to the fact that I have created pictorial immaterial states,

Due to the fact that I have manipulated the forces of the void,

Due to the fact that I have sculpted with fire and with water and have painted with fire and with water,

Due to the fact that I have painted with living brushes — in other words, the nude body of live models covered with paint: these living brushes were under the constant direction of my commands, such as “a little to the right; over to the left now; to the right again, etc.” By maintaining myself at a specific and obligatory distance from the surface to be painted, I am able to resolve the problem of detachment.

Due to the fact that I have invented the architecture and the urbanism of air — of course, this new conception transcends the traditional meaning of the terms “architecture and urbanism” — my goal from the beginning was to reunite with the legend of Paradise Lost. This project was directed toward the habitable surface of the Earth by the climatization of the great geographical expanses through an absolute control over the thermal and atmospheric situation in their relation to our morphological and psychical conditions.

Due to the fact that I have proposed a new conception of music with my “monotone-silence-symphony,”

Due to the fact that I have presented a theater of the void, among countless other adventures…

I would never have believed, fifteen years ago at the time of my earliest efforts, that I would suddenly feel the need to explain myself — to satisfy the desire to know the reason of all that has occurred and the even still more dangerous effect, in other words — the influence my art has had on the young generation of artists throughout the world today.

It dismays me to hear that a certain number of them think that I represent a danger to the future of art — that I am one of those disastrous and noxious results of our time that must be crushed and destroyed before the propagation of my evil completely takes over.

I regret to reveal that this was not my intention; and to happily proclaim to those who evince faith in the multiplicity of new possibilities in the path that I prescribe — Take care! Nothing has crystallized as yet; nor can I say what will happen after this. I can only say that today I am no longer as afraid as I was yesterday in the face of the souvenir of the future.

An artist always feels uneasy when called upon to speak of this own work. It should speak for itself, particularly when it is valid.

What can I do? Stop now?

No, what I call “the indefinable pictorial sensibility” absolutely escapes this very personal solution.

So…

(continue)

Hye Yeon Nam: Walking, Drinking, Eating & Sitting

Posted: August 22, 2011 Filed under: 2010-, Korea, Uncategorized, USA, Video & Film | Tags: Hye Yeon Nam Leave a comment Vodpod videos no longer available.

My work explores social issues based on personal experience. As a woman and a Korean immigrant in the United States, I have struggled to adjust to my new culture. Every situation summons different customs, requiring me to adopt unfamiliar behaviors in order to conform to expectations. My work reflects my desire to resist such pressure by using physical dissonance to reveal different perspectives upon the “norm.”

Art is not meant to be merely decorative or beautiful; instead, it can be a question, an argument, a proposal, a resolution. By addressing the everyday challenges that beset us all, my work strives to encourage others to confront social concerns and constraints and to seek to surmount them.

Encounter, National Portrait Gallery

Blinky Palermo: I have no programme

Posted: August 10, 2011 Filed under: 1970-9, abstract, Conceptual, Germany, minimal, Painting | Tags: Blinky Palermo, DIA Leave a comment

“I pursue no specific direction in the sense of a style. I have no programme. What I have is an aesthetic concept, whereby I try to keep as many expressive options open for myself as possible.”

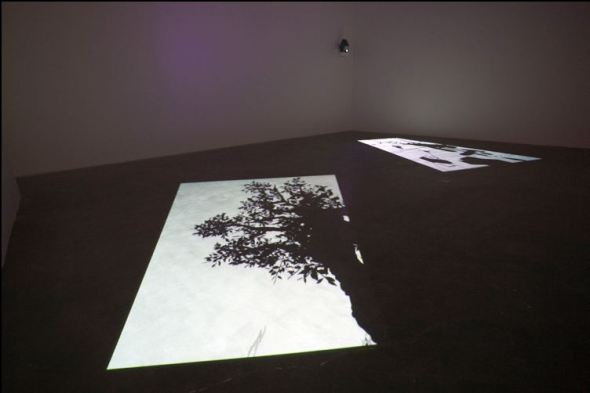

Paul Chan: What art is and where it belongs

Posted: August 6, 2011 Filed under: 2000-9, Conceptual, Installation, multimedia, USA, Video & Film | Tags: Paul Chan Leave a comment

How is art less than a thing? A thing, like a table, helps us belong in the world by taking on the essential properties of what we want in a table. It does not matter whether it is made of wood or steel, or whether it has one leg or four. As long as it is endowed with purpose, so that a table inhabits its “table-ness” wholly, to not only give us a surface on which to eat, or write, or have sex, but also to substantiate that purpose as the external embodiment of our will. In a sense, a thing is not itself until it contains what we want. Once it becomes whole, a thing helps us differentiate it from all that it is not. A chair may act like a table, enabling us in a pinch to do all the things a table can. But it is only acting. A thing’s use is external to its nature. And what is essential to a table’s nature is that all the parts that make up a table become wholly a table, and not a chair, or a rose, or a book, or anything else.

In art, the parts do not make a whole, and this is how a work of art is less than a thing. Like the perfect crime or a bad dream, it is not apparent at all how the elements come together. Yet they nevertheless do, through composition, sometimes by chance, so that it appears as if it were a thing. But we know better, since it never feels solid or purposeful enough to bear the weight of a real thing. This is not to say that art does not really exist or that it is just an illusion. Art can be touched and held (although people usually prefer you not to). It can be turned on or off. It can be broken. It can be bought and sold. It can feel like any other thing. Yet in experiencing art, it always feels like there is a grave misunderstanding at the heart of what it is, as if it were made with the wrong use in mind, or the wrong tools, or simply the wrong set of assumptions about what it means to exist fully in the world.

This is how art becomes art. For what it expresses most, beyond the intention of the maker, the essence of an idea, an experience, or an existence, is the irreconcilability of what it is and what it wants to be. Art is the expression of an embodiment that never fully expresses itself. It is not for lack of trying. Art, like things, must exist in a material reality to be fully realized. But unlike things, art shapes matter—which gives substance to material reality—without ever dominating it. All matter absorbs the manifold forces that have influenced how it came to be, and the uses and values it has accrued—and emanates the presence of this history and its many meanings from within. In a sense, form is just another word for the sedimented content that smolders in all matter. Art is made with sensitivity to and awareness of this content. And the more the making becomes attenuated, the more art binds itself to the way this content already determines the reality of how matter exists in the world. This reality, or nature, is the ground art stands on to actualize its own reality: a second nature. But it is never real enough, since the first nature will never wholly coincide with the second.

What art ends up expressing is the irreconcilable tension that results from making something, while intentionally allowing the materials and things that make up that something to change the making in mind. This dialectical process compels art to a greater and greater degree of specificity, until it becomes something radically singular, something neither wholly of the mind that made it, nor fully the matter from which it was made. It is here that art incompletes itself, and appears.

The irony is that because it cannot express what it truly wants to be, art becomes something greater and more profound. Its full measure reaches beyond its own composition, touching but never embracing the family of things that art ought to belong to, but does not, because it refuses (or is unable) to become a thing-in-itself. Instead, art takes on a ghostly presence that hovers between appearance and reality. This is what makes art more than a thing. By formalizing the ways in which objective conditions and subject demands inform and change each other over the course of its own making, a work of art expresses both process and instant at once, and illuminates their interdependence precisely in their irreconcilability. And it is as a consequence of this inner development that art becomes what it truly is: a tense and dynamic representation of what it takes to determine the course of one’s own realization and shape the material reality from which this self-realization emerges. In other words, whatever the content in whatever the form, art is only ever interested in appearing as one thing: freedom.

(excerpt read full statement)

A Dialogue about the Moving Image

Eric Desmarais: Sound Installation?

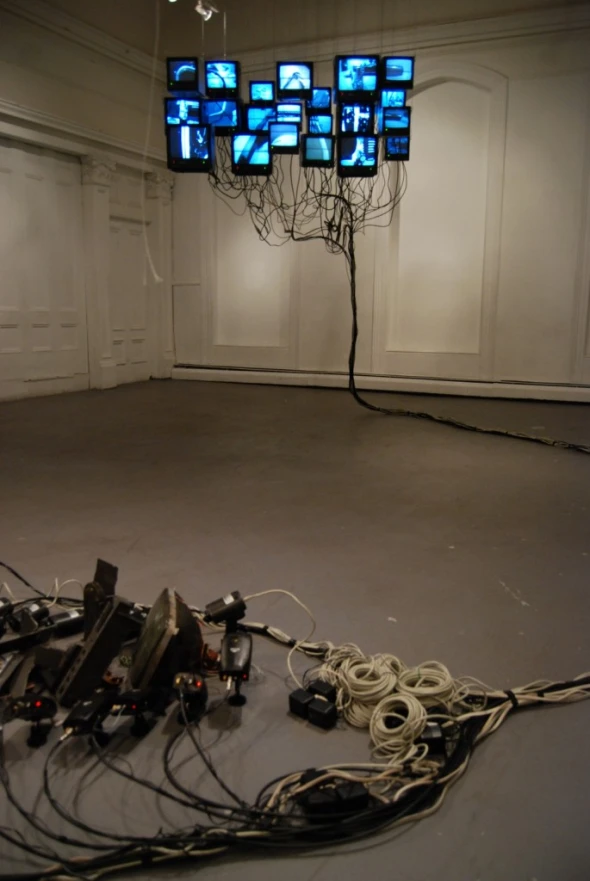

Posted: July 13, 2011 Filed under: 2010-, Canada, Installation | Tags: Eric Desmarais Leave a comment

The installation: Le mot traduit le bruit des contingences passées [“The Word Reflects the Noise of Past Contingencies”] is based mostly on sonic concerns. Although its form and the elements used in it all point toward what should be a video installation, the work actually highlights the main feature of sound: its evanescence. Sound exists only in an instantaneous temporality. Through an attempt at playfully piecing back together a vanished sound event, the installation sets a series of ambiguous relationships between sounds and pictures, past time and present time, unique perspective and mobile perspective. Surveillance cameras and monitors – the guards of our relationship to the present time and our fantasies of omniscience and ubiquity – spy the inanimate shards of one of their own, heavily fallen from the ceiling, taking with it the sound of a past event. Inescapably, time dissipates the clamour of the noisiest events… Lacerated matter – the sole clue of the event’s violence – contains in itself the trace of a noisy transformation of matter. Through multiple perspectives on the remains of this incident, the work makes sound reappear. The sound is not reproduced; it is suggested, implied; it is written. So the installation transforms sound into picture, pictures into word, and word into sound. Therefore, the work addresses a number of issues in relation to temporality and mobility, through a series of cognitive games and back-and-forths between moving images, real time, sound, multiple perspectives, and a single perspective. Are we in the presence of a sound work, despite the physical absence of sound?

Julian Opie

Posted: June 12, 2011 Filed under: 2010-, England, figurative, landscape, Painting | Tags: Julian Opie Leave a comment

Well that is what I do – I draw. Drawing is a process of making equivalents – of engaging in the world physically and emotionally – of casting your mind out and grasping what you see. To me it’s as natural as walking or talking – I have been doing it since I was 11 – every day – I cannot explain any one drawing as it depends on the one before. I suppose this is the way I see the world – it’s the closest I can get to reality. (read)